Originally published on January 9, 2015

Did You Know that Many Advertising Claims are Literally True but Still Misleading?

What if I told you that my brand of headache medicine may make your headache go away faster than another leading brand, such as Excedrin? What would you take my claim to mean? If you are like most people, you will take the word “may” to mean ‘probably will’ or simply will. However, that is not really what the word “may” means. May means maybe. As in maybe my headache medicine will work faster and maybe it will not.

So, you see, if my headache medicine works faster than the leading brand in even a very small percentage of cases, I am not lying. It is “literally true” that it may work faster for you and it may not. It doesn’t matter that “may not” is more likely. If accused of being deceitful, I can say I was not lying. I said may. However, I am being deceitful, am I not? What I say is technically true but misleading.

See also: Be Aware of PLR (Private Label Rights) Fitness Articles That May Mislead You

Sure, I’m literally telling the truth so you’d have a hard time successfully suing me. I’m counting on your favorable interpretation of my claim. Enough people will translate the word may to the word does for my advertising claim to be effective. My medicine, they will read, does relieve your headache quicker than Excedrin.

While false claims advertising claims about fitness and health problems are common, these kinds of literally true but misleading claims the health, fitness, and nutrition industries are even more common. You probably saw several instances of such claims today without realizing it.

What if I was even more sneaky? What if I just said my medicine works better? You would assume that I meant that my headache medicine works better than other such medicines. But I never say that. I just say it works better. If it is literally true that my medicine works better than a sugar pill, for example, I am “not lying.” This is a “piecemeal” claim because I am implying a comparison without actually comparing anything, while counting on you to feel in the blanks in a way that works for me, but misleads you.

Such literally true but misleading claims are easy to make in nutrition claims for food products. There are numerous examples. If you hear, for example, that a certain food product has reduced fat, you might take that to mean it is low fat, even if the product does not actually qualify for a low-fat claim on its label. Even if the fat content had been reduced by a paltry gram, the claim would still be literally true.

The FTC, in 1994, ordered Stouffer’s Food Corp. to stop making certain misleading claims about its Lean Cuisine Frozen Entrees. Lean Cuisine ads at the time said “Some things we skimp on: Calories. Fat. Sodium…always less than 1 gram of sodium per entree.”

What an unwary consumer may not have realized is that a gram of sodium is a boat-load! We measure dietary sodium in milligrams, not grams. A milligram is one-thousandth of a gram. Although a gram might seem like a very small amount, when it comes to sodium it is a huge amount. The fact is that meals contained something like 850 milligrams of sodium. That’s a third of your ‘recommended’ daily sodium. For a person who does need to be on a salt restricted diet, such as one whose high blood pressure is aggravated by dietary sodium, this claim could be misleading. The entrees did not really qualify to be labeled as low sodium, but the ads implied they were low sodium. The claims were literally true, but completely misleading. Later, the FTC expanding the ruling to include claims about fats and other ingredients. In order to make a statement about low sodium, the sodium content must be less than 140 milligrams of sodium.

This is also an example of using numbers to mislead. I wrote about numbers and how they can deceive us in Average Deadlift Weight: How Numbers Lie in Fitness Advertising and Info.

What if I said that my restaurant’s signature burger has less fat than a Big Mac? What if, in fact, it only had 2 grams less fat? Would the average consumer think that I was claiming such a low difference? Of course not. KFC once claimed that two of its original recipe breasts had less fat than a Burger King Whopper. It was true. The Whopper had 43 grams of fat, and the chicken had 38 grams. The chicken also had more calories and sodium. Yet, the television ads implied that Kentucky Fried Chicken was a “healthy food option” compared to something like a Burger King Whopper.

Misleading to Whom?

So, when claims are technically true, or literally true, but could still be misleading, who, exactly are they misleading to? Are we talking about one person who was misled? Are we talking about the majority of consumers? Do we mean a quite skeptical consumer who is extremely diligent in their decision-making process? Or, do we mean a very gullible consumer or a generally reasonable consumer? As well, it is necessary that any consumers were actually misled by such a claim?

In all of these cases, what should be understood is that the honesty of ads must be judged not on their literal truth, but on how the consumers will understand the ads. Regardless of the specific language used in the ad, what is important is what the advertisement conveys to reasonable consumers. It does not matter whether you can prove that any consumers were misled or not mislead, only that the reasonable potential for being misled exists. You can be sure that when companies make such claims, they use focus groups and other marketing research to gain an understanding of just how the ads will be understood by the public.

Realize that these types of claims are much different than the kind of “tall tale” bragging claims typically known as puffery. For example, Papa Johns pizza was able to get away with saying “Better Ingredients, Better Pizza” (than Pizza Hut) because the courts decided it was puffery, meaning that the average consumer would dismiss the claims as simple overstated bragging, and would not be likely to take them seriously. I happen to think that many of Papa John’s early claims were much more than puffery, and were deceptive. However, it is likely that most people will not take their advertising slogan to be “literally true.”

The way we interpret certain words is the key in these types of deceptive advertising messages. Let’s look at one such term that is often used in fitness and weight loss advertising.

Example of Misleading Advertising: Unsurpassed!

“My new diet is unsurpassed in its weight loss results.” Doesn’t that sound impressive? Here is another: “The StrengthMinded Strength Training Program is Unsurpassed in its Ability to Cause Quick and Substantial Gains in Muscular Strength.”

Most people see “unsurpassed” as meaning the same as “unequaled.” In other words, the weight loss diet claim will likely be interpreted as meaning that no other diet provides results as good as this diet.” And, the GUS strength program claim will likely be interpreted to mean that no other program will get you as strong as quickly.”

However, in both cases, the claims are literally saying that they are only as good as any existing alternative. Merriam-Webster defines the term unsurpassed as “having no equal or rival for excellence or desirability” or “of the very best kind.” The second definition is the one I’m relying on to make my claim. It means that other methods or products are not better than this method or product. If my product is at least as good as the alternative products available I can use a powerful word like unsurpassed to imply that it is significantly better than the alternatives, without actually lying.

Misleading Fitness Ads

It would be hard to really prove what was the fastest possible result a person could get in a fitness or weight loss intervention. However, if I claim that my weight loss program delivers the “fastest results possible,” I could probably get away with it. Fastest results possible, after all, could be interpreted as a very reasonable thing to say, literally speaking. After all, if there is reasonable evidence to suggest that the typical leading weight loss solutions deliver a certain average result, and my product also delivers this same result, I could say that I interpret this as the fastest results possible within the realm of these types of products. I am saying, literally, that my product is just like all the rest. No better, no worse. However, fastest results possible will usually be interpreted as faster results.

Now, compare this with the following:

“The StrengthMinded Strength Training Program is the Best in the World.”

Do you see the difference? Not many people will believe this claim. They will see it is a blatant exaggeration or puffery. They will dismiss it out of hand. A person that is misled by such a claim is probably not a reasonable person. A child would be more vulnerable, for example, to such a claim, than most adults.

You know that elves who live in trees do not make Keebler cookies. This is not false advertising, its just clever marketing. A reasonable person would not base his or her cookie purchase on a belief that friendly tree elves baked the cookies fresh each day.

Puffery, as well, are the various claims of breakthrough weight loss, fitness, or strength training products or programs. Who would take such claims seriously?

However, what if the claims are a bit more specific. Surely, you wouldn’t believe me if I told you my strength program was superior to all other programs. But what if I told you that “I have seen scientific reports that this method is superior to other methods.” What if, I had literally heard from a ‘scientist’ or two, that such and such a thing was superior but I had, in reality, no reliable scientific evidence to support my claim? I am not lying about these ‘reports.’ My statement is literally true, but what I didn’t tell you is that the scientists were personal friends in non-related fields who have blogs on strength training. Most people would tend to take my statement as claiming scientific studies. Thus, my statement is literally true but misleading. This is about substantiation.

The truth is that MOST claims made in fitness are unsubstantiated, even those based on credible underlying science. Even simple claims that seem innocent and unimportant help give rise to a culture in which such claims are easily accepted, even when they are quite important. For example, let’s say someone tells you that their muscle building routine for the chest will help bring out your upper pecs, especially since incline bench and flys are used. To explain this, they give you some kinesiological information about how the incline press works. You can read about the kinesiology of the incline bench press here at StrenghtMinded, as well. But, does this kinesiological information actually provide evidence or proof that the incline press or this particular routine being advanced actually causes the upper pectorals to grow preferentially? NO! No actual direct evidence is being offered that this is true, thus this claim is unsubstantiated. However, claiming that an explanation of the underlying kinesiology proves that the claim is true is misleading.

Let’s look at more common claims related to substantiation:

Doctor Recommended

If I tell you that my weight loss program is doctor recommended, you, as a consumer, expect me to have a good reason for saying that it is doctor recommended. You do not expect, for example, that I mean that one doctor in the entire world recommends my product. You will expect a certain level of support, and that I mean “a majority of doctors recommend this product.” You will also not expect that out of 100 doctors, 30 recommend my product, and 70 explicitly warn against it, calling it dangerous. Similarly, if I tell you that “Tests prove” my product works, it is not reasonable to assume I mean that 2 out 100 tests were positive. Notice that any of these claims may be literally true, but they are piecemeal claims and they do not have the reasonable level of substantiation that a typical consumer would expect.

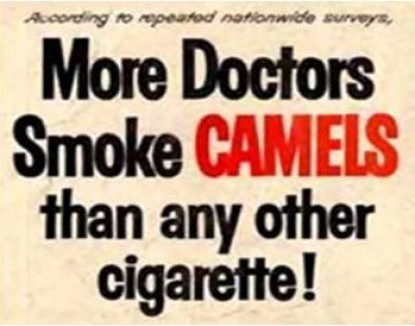

The old Camel cigarettes ad below is an easy to understand example of a misleading “statistic” that combines doctors and a misleading implied claim:

It may well have been true that of the doctors surveyed, more of them smoke Camels. The implication is that doctors smoke Camels because they think they are more healthy and that they would then recommend Camels to their patients for this reason.

Even more often, we see claims such as this:

“9 out of 10 doctors recommend brand x.”

It may be true, but what are some pertinent questions?

1. Were only 10 doctors surveyed? Would that not be an inadequate sample?

2. How were the doctors who participated in the survey chosen? Were they chosen at random from among a diverse pool of physicians? Or were they carefully selected for “whatever” reason?

3. What were they asked? “Doctor, if you had to choose between this here vitamin pill and a smack upside the head, which would you recommend?”

Endorsements can be another example of implied claims that not actually false, but the net implication is deceiving.

Endorsements: This Happened Along With This

“I used X whey protein and my bench press went up 30lbs!” Both of these things can be true. Notice that this endorsement (most of these types of endorsements are fake) does not actually say that the use of the whey protein caused the increase in the bench press. How could it? It only implies this. It is a bit like saying “I drank 8 glasses of water a day and now I’m cancer free!” Perhaps the chemotherapy had something to do with it.

7 Deceptive Fat Loss Claims to Look For

I mentioned “fastest results possible.” Many weight loss advertisements claim the fastest results possible, but not in the literally true but deceptive way I mentioned above. The FTC has compiled a list of what they call gut check claims. What they mean is that when you see these types of claims, you should “check your gut.” Does this sound likely to be true? Is it, indeed, too good to be true? Here are 7 such claims:

1. causes weight loss of two pounds or more a week for a month or more without dieting or exercise;

2. causes substantial weight loss no matter what or how much the consumer eats;

3. causes permanent weight loss even after the consumer stops using the product;

4. blocks the absorption of fat or calories to enable consumers to lose substantial weight;

5. safely enables consumers to lose more than three pounds per week for more than four weeks;

6. causes substantial weight loss for all users; or

7. causes substantial weight loss by wearing a product on the body or rubbing it into the skin.

When you see claims like this, they are ALWAYS false. Period. As should be clear by now, not all claims are so blatantly deceptive! You can easily see the difference between the claims above and the literally true but deceptive claims I am concerned with in this article.

Now, hopefully, you will be more aware of such tactics. They will probably jump out at you now that they are on your radar! Here, we are concerned not with express claims, which are clearly stated in advertising but implied claims. Therefore, we need not only be concerned with the language used but even the images that accompany the advertisement. Do the images, combined with the language, imply a certain claim? The next time you see a TV advertisement about a drug, notice the part where they talk about the dangers and side-effects of the drug. Do the images on the screen coincide with the message about the possible dangers? We must also be aware of the intended audience of the ad. Even though an ad may look like simple puffery to a reasonable adult, a child might interpret it differently. Therefore exaggerated claims aimed at children should not always be considered puffery.

When you TV commercials for toys, the toys are often made to look like they come with more accessories than they do and that they have more capabilities than they do. You might see an ad for a robot toy where the toy is shooting laser beams out of his eyes. As an adult, we know this is unreasonable puffery but does our 5-year-old know this?

Speaking of misleading claims (or in this case, false claims), you may also be interested in reading about biofeedback for strength training.