In the last section, I talked about how fitness pros use celebrity training routines as evidence of effective ways to train. I specifically described the craze over Hugh Jackman’s training to prepare for his roles as The Wolverine. In this section, I’ll dive a bit deeper into the concept of anecdotal evidence to provide a more general understanding of what it is and how we use it.

Previous: What Can the Wolverine Tell Us About Strength Training? | Table Of Contents

People use anecdotal evidence as a primary source of data all the time. In fact, many people tend to use it more often than they use more valid data. Some rely solely upon anecdotal data often dismissing everything but there own or someone else’s “personal experience”.

What is a Lack of Representativeness?

So, the title of this section suggests that there is a problem with anecdotal evidence that this is a “lack of representativeness”. What does that mean? It simply means that anecdotal evidence often, if not most often, fails to be a typical experience or scenario or fails to represent what would be true of a broader population or sample.

How can we say this? Doesn’t any story have a chance to be true for many people? Certainly it does. But those stories which tend to be presented as evidence are those stories that stand out in a our minds. As I said before, they are not typical. In fact, they are peculiar and unusual. Extraordinary, even. They stand out in our memories and our memories have faulty wiring when it comes to data. The stuff that is on top of the pile is accessed first and is deemed therefore to be more important and assumed to be more representative than it is. The classic example I always use is:

Do more people die in automobile crashes or from heart attacks each year?

Most people say automobile crashes. But in truth, the answer is heart attacks. We’ve all seen pile-ups on the side of the road with flashing blue lights galore but very few of us have actually known someone who has died of a heart attack. This creates a selection bias. Trump this with the fact that automobile crashes are more spectacular. Our mind creates the assumption then, based on the question, that more people must die in car crashes. We do not juggle the data well. There are many car crashes but most of them do not involve fatalities. We can’t make conclusions about a broader population based on anecdotal evidence.

More Examples of Using Anecdotal Evidence

Here is another example from the Australian Bureau of Statistics:

Even though you might not think about it often, you often make decisions in your life based on experiences that you have had or on things that you have heard about. In such cases, you are basing your decisions on anecdotal evidence.

Let’s say a friend of yours claims that a particular brand of inexpensive shower cleaner is really good. Your friend explains that he simply sprayed it on the tiles, left it for 10 minutes, and when he came back the tiles were spotless without him having scrubbed or done anything else! This anecdotal evidence is enough of a recommendation for you. You buy some and use it, thus testing the evidence for yourself.

Another example of anecdotal evidence occurs when we decide not to go to a particular area because we have heard that an isolated event such as a horrific crime has occurred there. However, there is an overwhelming body of evidence that we have a much greater chance of being seriously injured driving our car locally. Yet, we do not hesitate to get in a car and drive somewhere.

The first example is a more valid and natural way to use anecdotal evidence. The friend’s story is suggestive that the shower cleaner might work. But this is easily testable. We buy the product, we test it. Either it works or it doesn’t. Not many would buy it again if the test failed. Case closed.

The second scenario, however, is not testable. We will never know if there was any heightened risk involved in driving to the area where a bad crime occurred. And so statistics might tell us that there, in fact, is not.

Logical Thought vs. Rational Thought

However, there is a difference between logical thought and rational thought. Logic would tell us that we have more chance of having an accident close to home because the statistics point to that conclusion. Nevertheless, there are considerations other than pure logic. For instance, if we are highly anxious and fearful of driving and we know that driving into unknown areas, especially if there may be a chance of the area being dangerous, will heighten that anxiety, thus putting us at risk of making serious driving errors, then it may be a rational decision to not drive into this new area. If we don’t have a pressing need to make this drive and if not driving there does not impact our life negatively or the lives of others there is nothing to be sneered at.

Jamie Hale has discussed rationality in his article Critical Thinking: What is True and What to Do:

In it, he says that “Rationality is concerned with two key things: what is true and what to do (Manktelow, 2004). In order for our beliefs to be rational, they must be in agreement with evidence. In order for our actions to be rational, they must be conducive to obtaining our goals.”

So, there is nothing particularly irrational about believing, from a standpoint of self-knowledge, that we would be better off avoiding anxiety and nervousness when driving “if we can help it”. This is in line with our goal to both drive safely and avoid situations that heighten our state anxiety, especially given that we have a high trait anxiety! We can make that decision and still be detached enough to say “even though I know good and well that the statistics don’t lie”.

But the website above gives another scenario:

A friend of yours says he will never wear a seatbelt again. He explains that an acquaintance of his survived a car accident because she wasn’t wearing a seat belt. The acquaintance flew through the windscreen, landed on a grassy bank, and suffered minor injuries. Meanwhile, the car burst into flames and was destroyed.

You are not convinced by this story alone that it is a good idea to abandon wearing a seatbelt.

Here we have a need for PURE LOGIC. We can only rely on data of some kind. So as per the examples of possible research avenues you could:

a) Observe a busy street to see how many drivers involved in accidents are wearing seat belts.

b) make up the data so it supports your friend’s view that seat belts are a waste of time.

c) Conduct an experiment in which a number of drivers, half of which are wearing seat belts, drive into a brick wall.

d) Examine a large number of accident reports to see whether survivors were wearing seat belts or not.

1. Choice A seems logical. But ONE street is not representative. There is not enough data to be gathered

2. Choice B would be a popular choice for many, especially if the friend was like a bodybuilding or strength training guru! In this case, a rationalization would have taken place as to how the friend must be right and a belief would be cemented with a pre-rationalization. And due to the power of belief perseverance, no amount of hard data would sway us

3. Choice C is how most people conduct their training

4. Choice D is the correct choice.

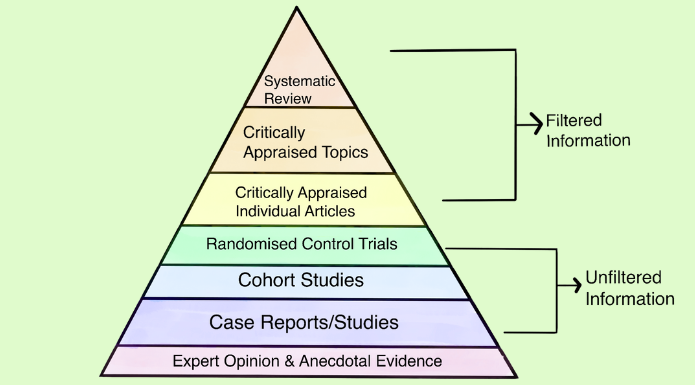

This horrifying story of a friend being thrown through a windshield to relative safety while her care blows up is, while dramatic, almost unheard of. To be thrown through a windshield would normally result in grievous bodily injury including brain trauma. This is to say nothing of the impact one would suffer upon landing. As well, cars rarely if ever actually start on fire or ‘blow up’ after a crash. This is Hollywood fiction. Seeking out actual statistical and scientific data can help keep us safe, while dramatic stories may cause us to believe unreasonable and dangerous things.